Chapter 7 Hypothesis testing

7.1 A quick refresher

Hypothesis testing is a way of validating if a claim about a population (e.g. a data set) is correct. Getting data on a whole population (e.g. everyone in Australia) is hard - so to validate a hypothesis, we use random samples from a population instead.

The language when dealing with hypothesis testing is purposefully janky.

When looking at the outputs of our hypothesis test, we consider p-values. Note: There’s lots wrong with p-values that we won’t bother getting into right now. The long story short is if you make your null hypothesis ultra specific and only report when your p-value on your millionth iteration of a test is below 0.05… bad science is likely to get published and cited.

What we need to know:

A small p-value (typically < 0.05) indicates strong evidence against the null hypothesis, so we reject it.

A large p-value (> 0.05) indicates weak evidence against the null hypothesis, so you fail to reject it.

Let’s load in some packages and get started.

# Load in packages

library(ggridges)

library(ggplot2)

library(forecast)

library(ggrepel)

library(viridis)

library(readxl)

library(hrbrthemes)

library(dplyr)

library(stringr)

library(reshape)

library(tidyr)

library(lubridate)

library(gapminder)

library(ggalt)

library(purrr)

library(scales)

library(purrr)

library(aTSA)

library(readrba)7.2 T-testing our first hypothesis

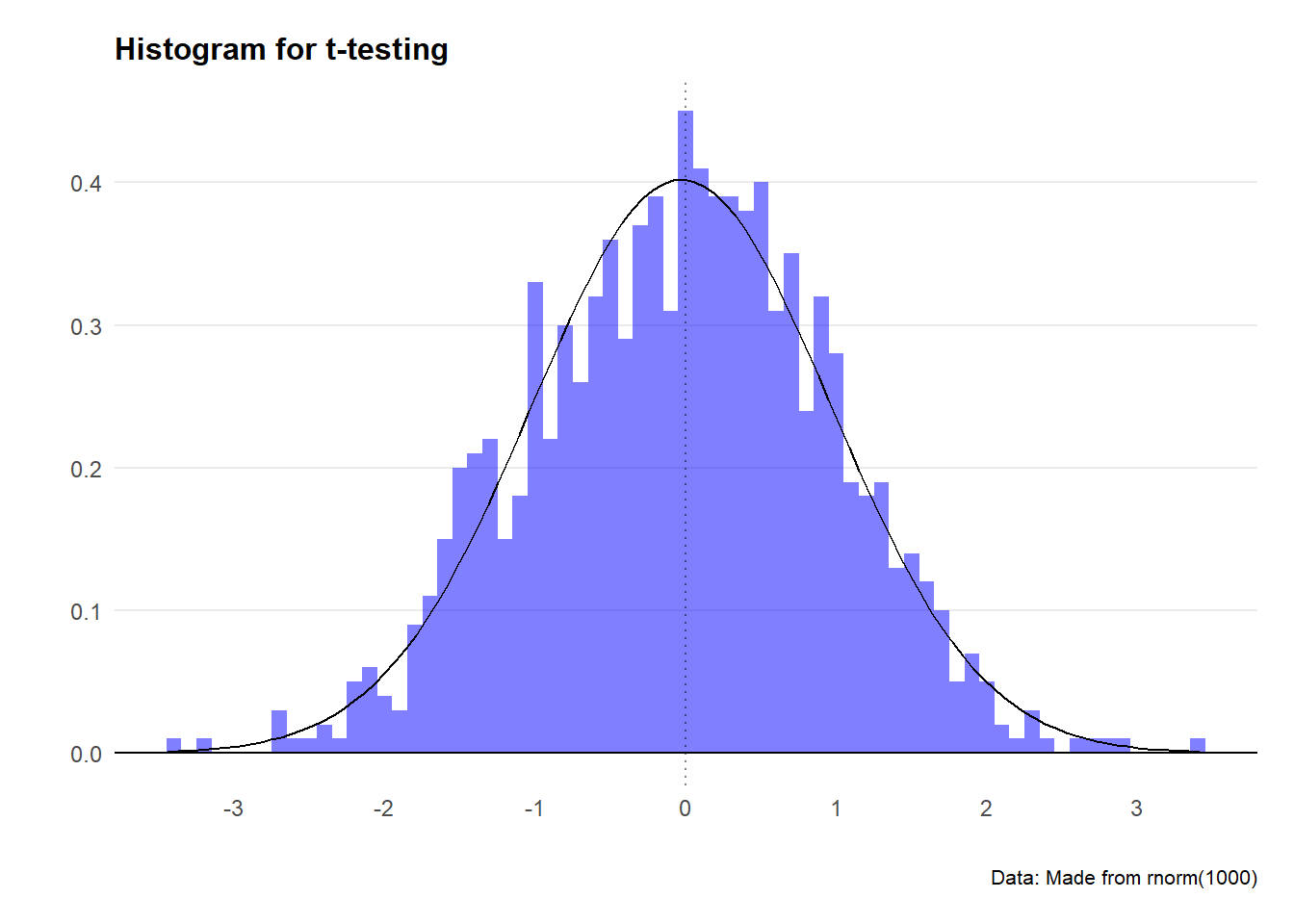

We’ll start simple. Let’s create a random dataset - with the caveat that it will be normally distributed. By default the rnorm function will generate a dataset that has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

set.seed(40)

dataset1 <- data.frame(variable1=rnorm(1000,mean=0,sd=1))

ggplot()+

geom_histogram(aes(x=dataset1$variable1,y=..density..),binwidth=0.1,fill="blue",alpha=0.5) +

stat_function(fun = dnorm,

args = list(mean = mean(dataset1$variable1), sd = sd(dataset1$variable1)))+

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0, linetype="dotted",alpha=0.5)+

labs(title="Histogram for t-testing",

caption = "Data: Made from rnorm(1000)",

x="",

y="") +

theme_minimal() +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(-3, 3, by = 1))+

theme(panel.spacing.x = unit(10, "mm"))+

theme(legend.position="none")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=9))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(plot.subtitle = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,15,0))) +

theme(plot.margin=unit(c(0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5),"cm"))

We know by default that the mean of dataset1 will be approximately zero… but let’s check anyway.

# Find the mean of dataset1

mean(dataset1$variable1)Great, now let’s run our first hypothesis test. We’ll use the t.test function. This is in the format of t.test(data, null_hypothesis).

So quite simply, we can test the null hypothesis that the mean for dataset1$variable1 is 5).

# Hypothesis test

t.test(dataset1$variable1, mu = 5)We see the p-value here is tiny, meaning we reject the null hypothesis. That is to say, the mean for dataset1$variable1 is not 5.

Going further, let’s test the hypothesis that the mean is 0.01.

# Hypothesis test

t.test(dataset1$variable1, mu = -0.03, alternative="greater")We see here the p-value is greater than 0.05, leading us to fail to reject the null hypothesis. In a sentence, we cannot say that the mean of dataset1$variable1 is different to 0.01.

7.3 Tailed tests

In the previous level we were cheating slightly, in that we didn’t specify the ‘tail’ for the test, or our confidence level. By default the t.test function assumes tests are two tailed, and the desired confidence level is 0.95 (i.e. 95%). However, in some cases we might want to have a hypothesis that says one variable is greater than or less than another variable (rather than just different from each other). This is where we use tails.

# Hypothesis test

t.test(dataset1$variable1, mu = 0.03, alternative = "greater")7.4 Correlation (and working with normal distributions)

A correlation coefficient measures the direction and strength of the correlation between two variables.

The tricky thing is - if variables aren’t normally distributed, none of our correlation theory works very well.

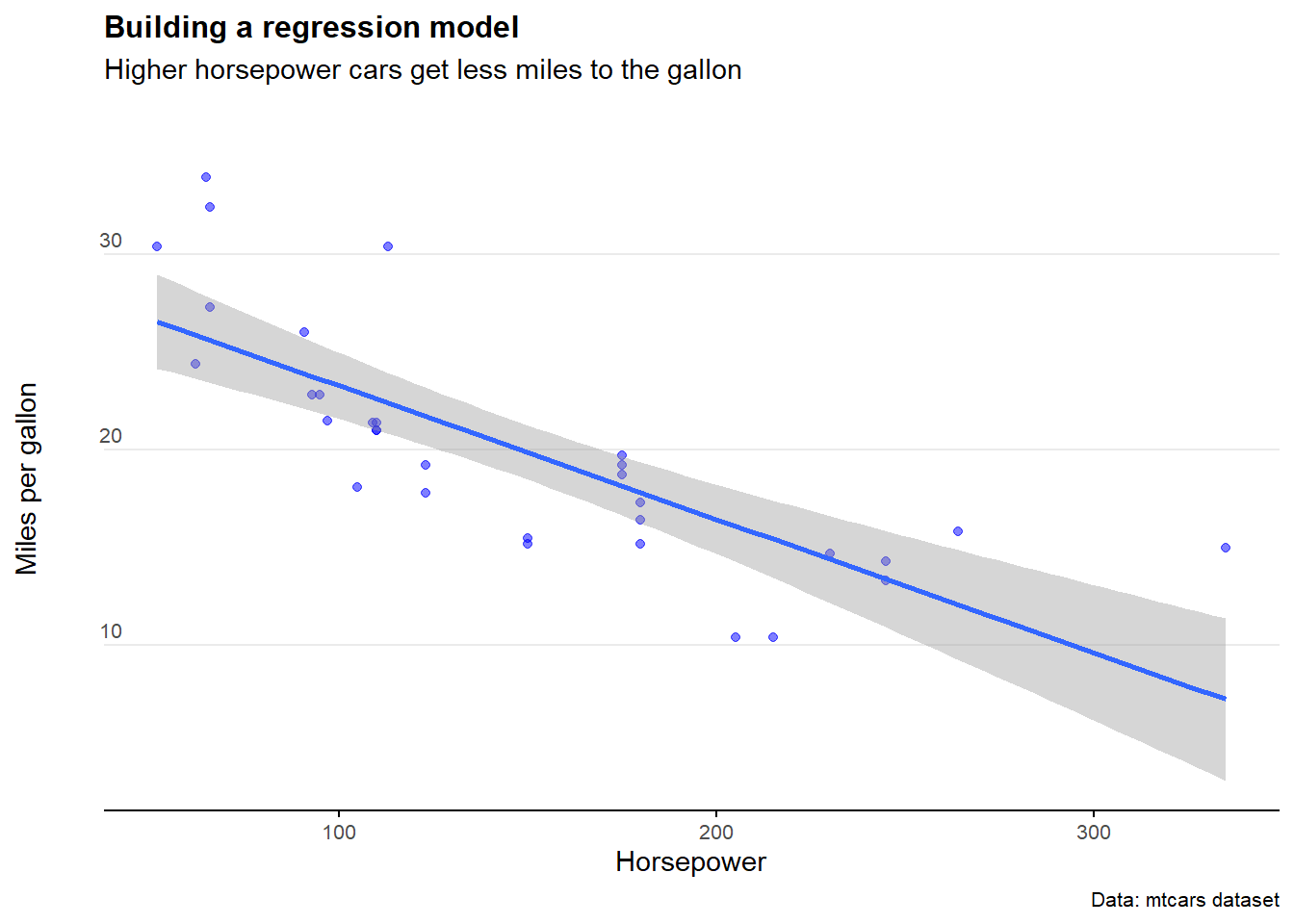

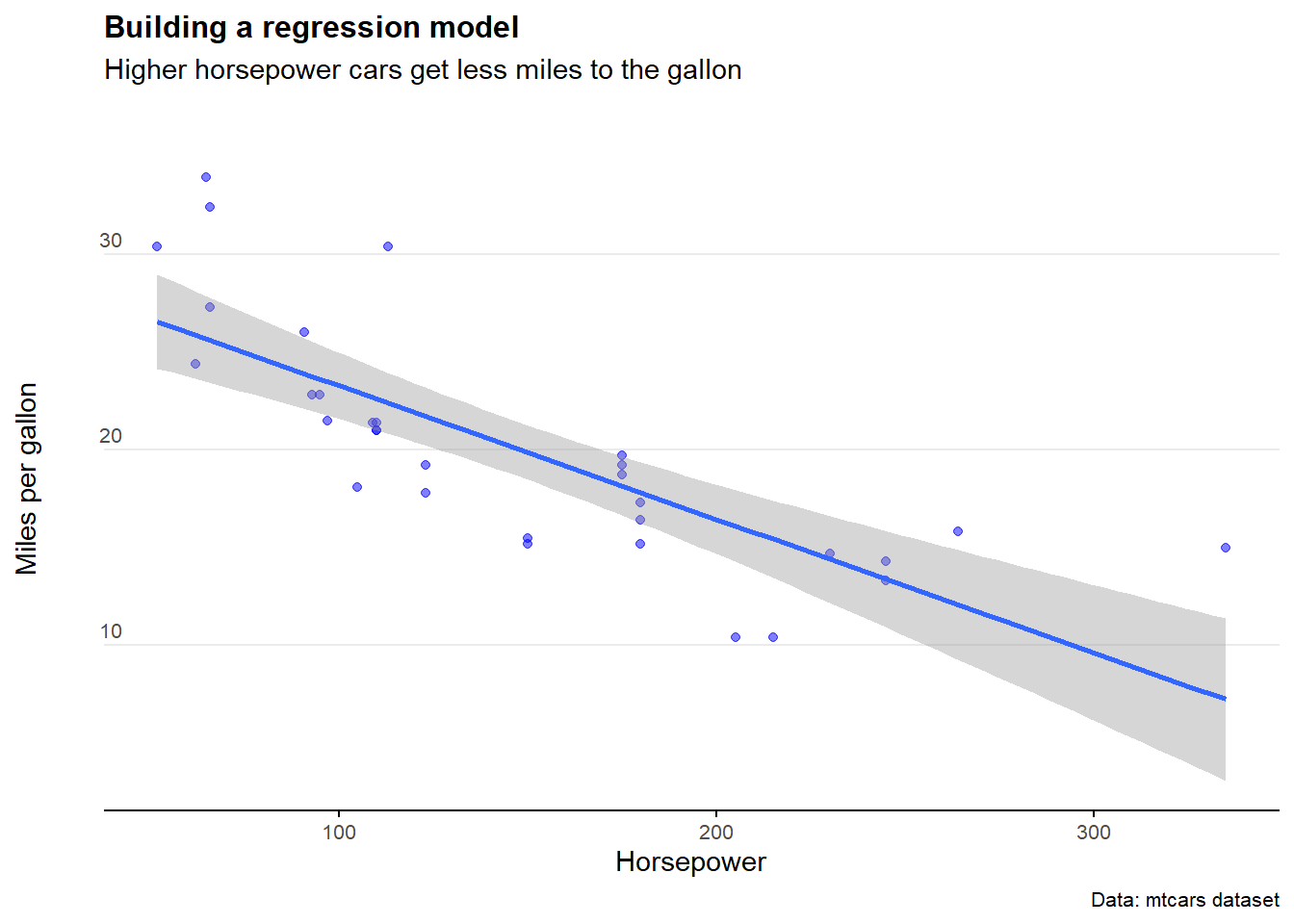

In the example below, we see that miles per gallon is correlated with horsepower. It’s a negative relationship, meaning the more horsepower in a car, the less miles per gallon the car exhibits.

ggplot(mtcars)+

geom_point(aes(x = hp, y = mpg), col = "blue", alpha=0.5)+

geom_smooth(aes(x = hp, y = mpg),method='lm')+

labs(title="Building a regression model",

subtitle = "Higher horsepower cars get less miles to the gallon",

caption = "Data: mtcars dataset",

x="Horsepower",

y="Miles per gallon") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position="bottom")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=8))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(axis.title.y =

element_text(margin = ggplot2::margin(t = 0, r = 3, b = 0, l = 0)))+

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(vjust = -0.5,

margin = ggplot2::margin(l = 20, r = -10)))+

theme(plot.subtitle = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,25,0))) +

theme(axis.line.x =

element_line(colour ="black",size=0.4))+

theme(axis.ticks.x = element_line(colour ="black",size=0.4))+

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position="bottom")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=8))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(axis.title.y =

element_text(margin = ggplot2::margin(t = 0, r = 3, b = 0, l = 0)))+

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(vjust = -0.5,

margin = ggplot2::margin(l = 20, r = -10)))+

theme(plot.subtitle = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,25,0))) +

theme(axis.line.x =

element_line(colour ="black",size=0.4))+

theme(axis.ticks.x = element_line(colour ="black",size=0.4))

We can use the cor.test to tell us the correlation coefficient and the p-value of the correlation.

We specify the method as ‘pearson’ for the Pearson correlation coefficient. But we remember this method only works well if both our variables are normally distributed.

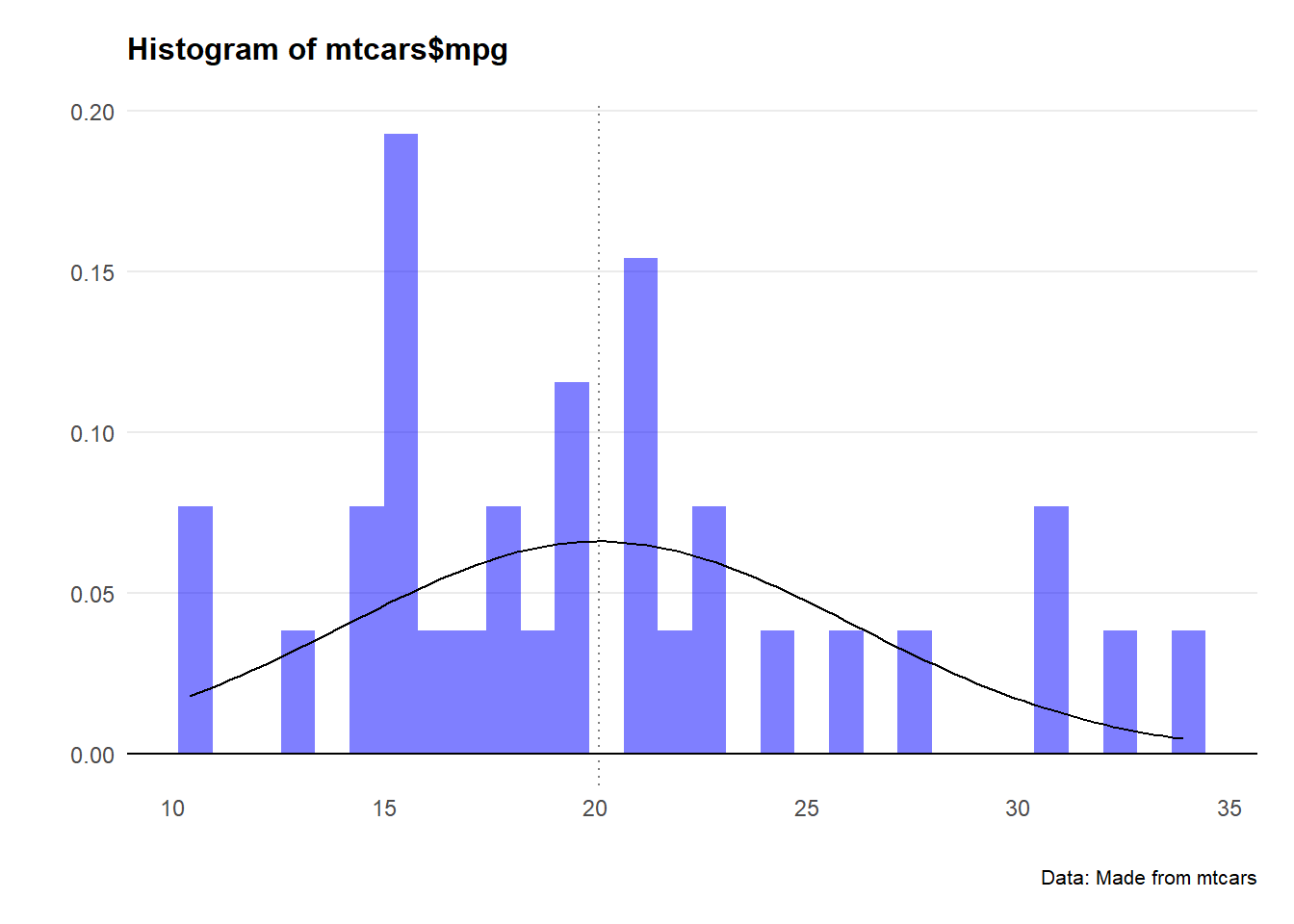

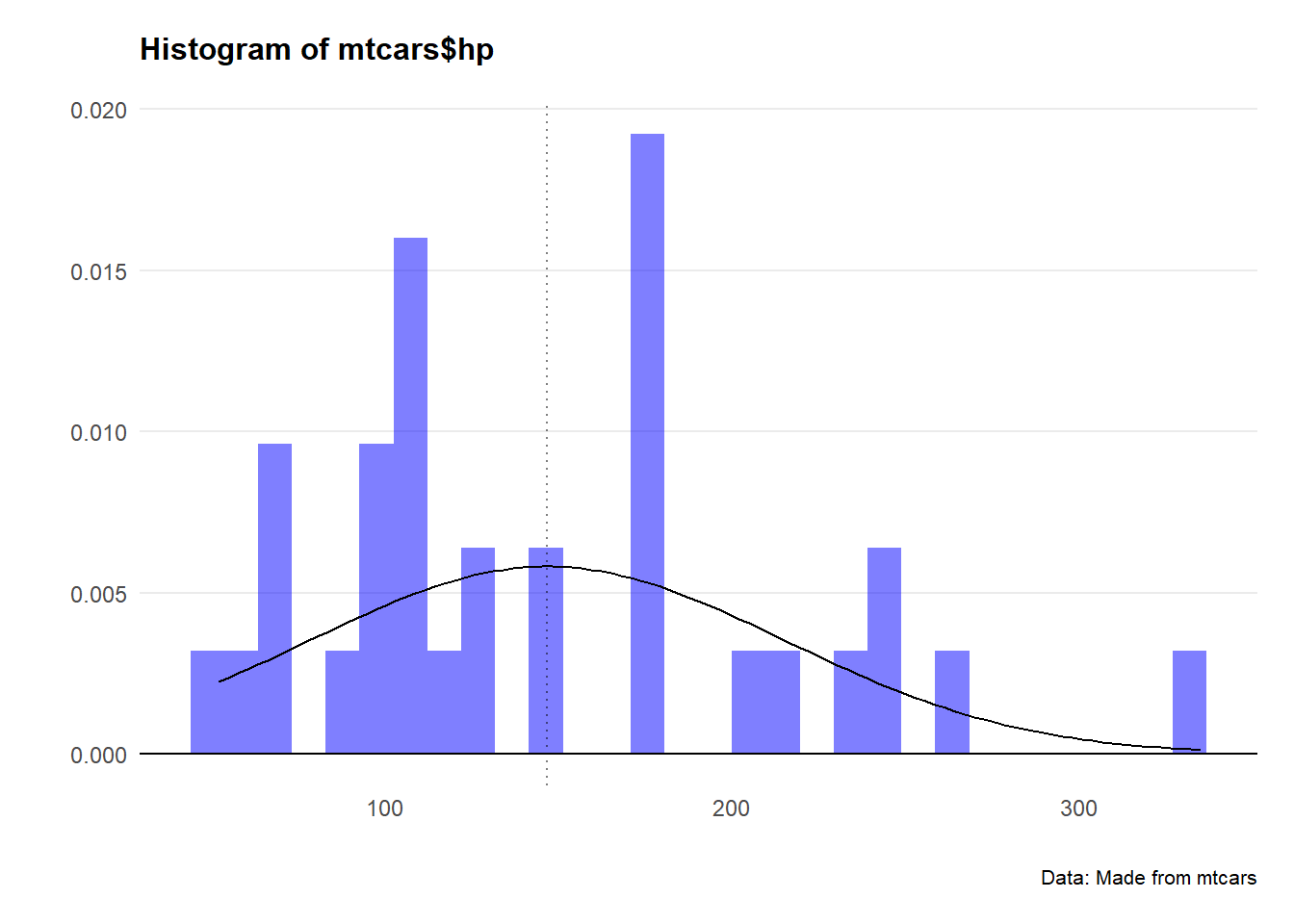

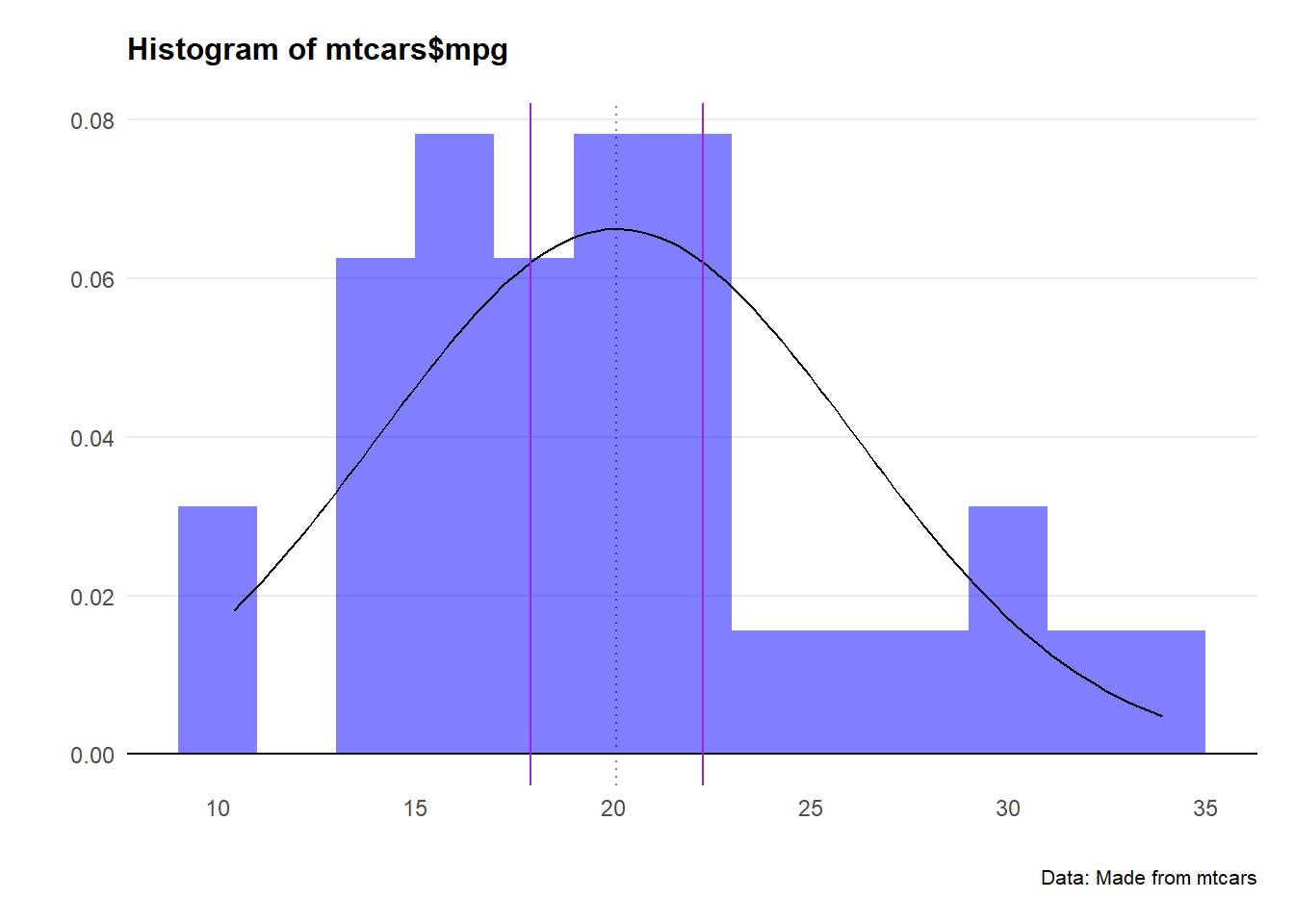

That’s worth checking - let’s plot a histogram for both hp and mpg.

cor.test(mtcars$hp, mtcars$mpg, method="pearson")ggplot()+

geom_histogram(aes(x=mtcars$mpg,y=..density..),fill="blue",alpha=0.5) +

stat_function(fun = dnorm,

args = list(mean = mean(mtcars$mpg), sd = sd(mtcars$mpg)))+

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean(mtcars$mpg), linetype="dotted",alpha=0.5)+

labs(title="Histogram of mtcars$mpg",

caption = "Data: Made from mtcars",

x="",

y="") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(panel.spacing.x = unit(10, "mm"))+

theme(legend.position="none")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=9))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(plot.title = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,15,0))) +

theme(plot.margin=unit(c(0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5),"cm"))

ggplot()+

geom_histogram(aes(x=mtcars$hp,y=..density..),fill="blue",alpha=0.5) +

stat_function(fun = dnorm,

args = list(mean = mean(mtcars$hp), sd = sd(mtcars$hp)))+

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean(mtcars$hp), linetype="dotted",alpha=0.5)+

labs(title="Histogram of mtcars$hp",

caption = "Data: Made from mtcars",

x="",

y="") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(panel.spacing.x = unit(10, "mm"))+

theme(legend.position="none")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=9))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(plot.title = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,15,0))) +

theme(plot.margin=unit(c(0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5),"cm"))

Crikey… they don’t look very normal at all.

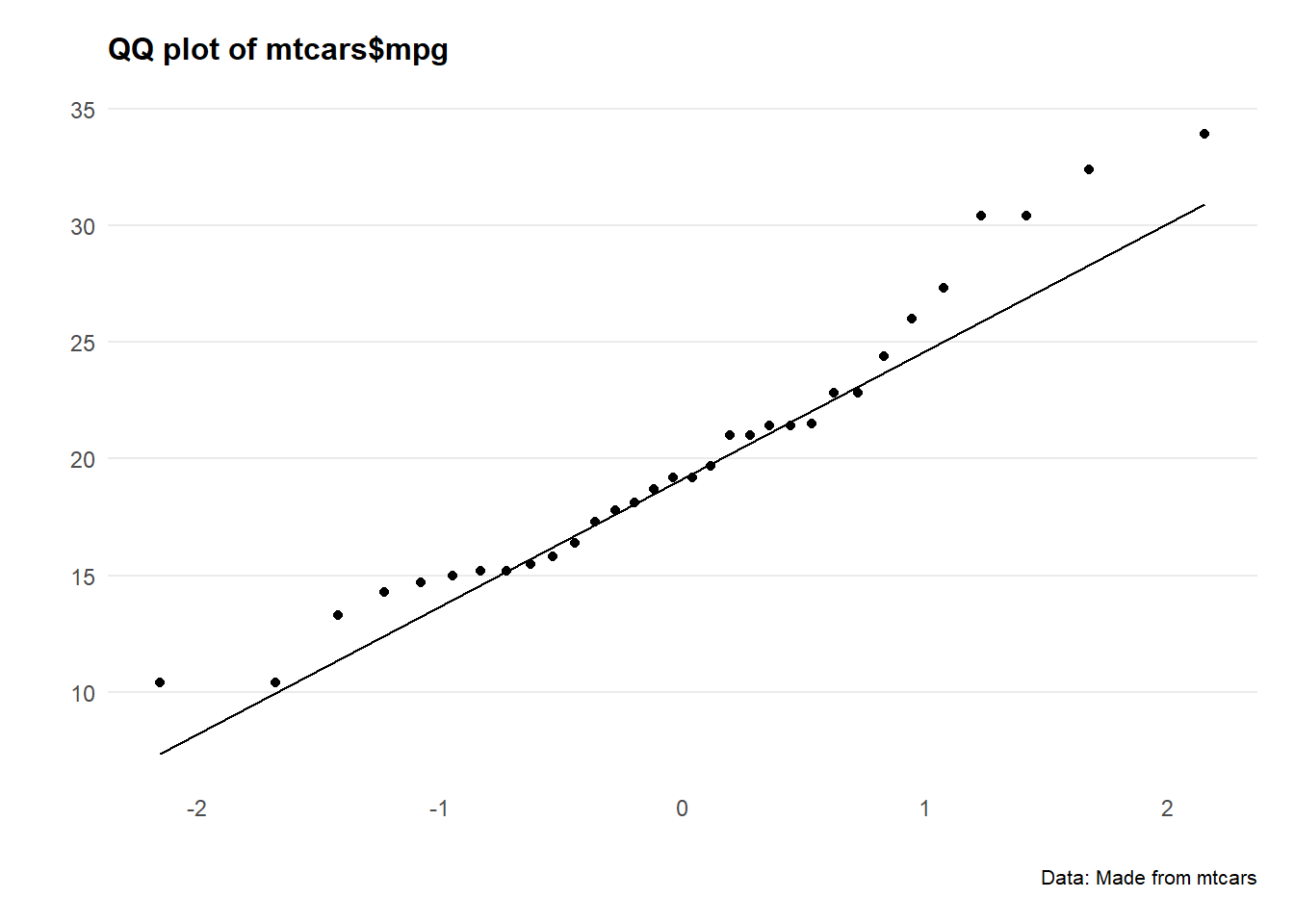

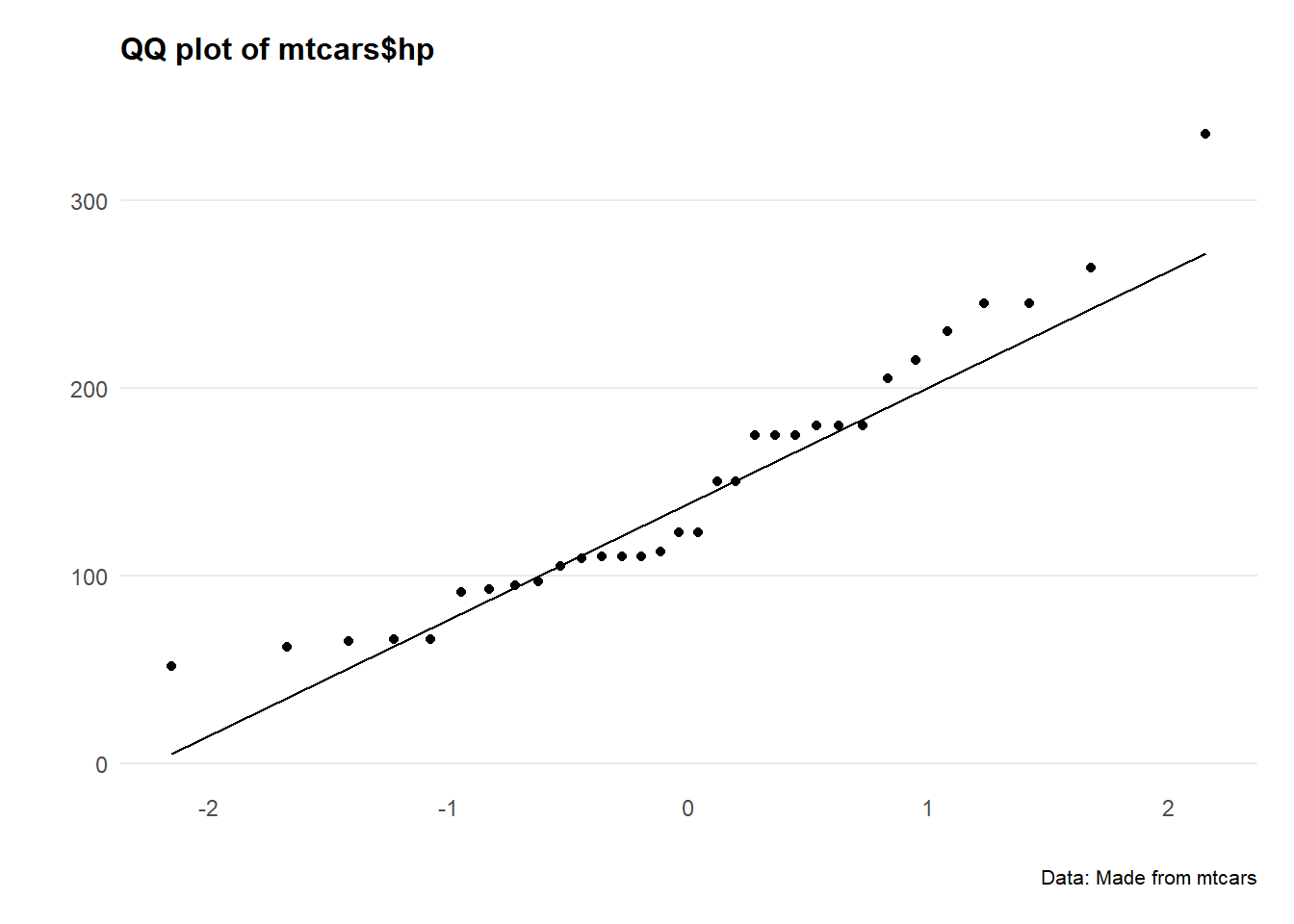

Let’s plot QQ plots of our variables and see what’s going on.

ggplot(mtcars, aes(sample = mpg)) +

geom_qq()+

geom_qq_line()+

labs(title="QQ plot of mtcars$mpg",

caption = "Data: Made from mtcars",

x="",

y="") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(panel.spacing.x = unit(10, "mm"))+

theme(legend.position="none")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=9))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(plot.title = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,15,0))) +

theme(plot.margin=unit(c(0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5),"cm"))

ggplot(mtcars, aes(sample = hp)) +

geom_qq()+

geom_qq_line()+

labs(title="QQ plot of mtcars$hp",

caption = "Data: Made from mtcars",

x="",

y="") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(panel.spacing.x = unit(10, "mm"))+

theme(legend.position="none")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=9))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(plot.title = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,15,0))) +

theme(plot.margin=unit(c(0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5),"cm"))

Hmm okay, both series are a bit all over the shop.

Let’s do a statistical test to confirm.

The Shapiro-Wilk’s method is widely used for normality testing. The null hypothesis of this tests is that the sample distribution is normal. If the test is significant, the distribution is non-normal.

shapiro.test(mtcars$mpg)

shapiro.test(mtcars$hp)7.5 Confidence intervals (mean)

Firstly, we can calculate the confidence interval on a single variable. Essentially this measures the variance of the normal distribution, and gives us an idea of how ‘clustered’ the values are to the mean.

There are roughly 4 steps to do this:

Calculate the mean

Calculate the standard error of the mean

Find the t-score that corresponds to the confidence level

Calculate the margin of error and construct the confidence interval

mpg.mean <- mean(mtcars$mpg)

print(mpg.mean)

mpg.n <- length(mtcars$mpg)

mpg.sd <- sd(mtcars$mpg)

mpg.se <- mpg.sd/sqrt(mpg.n)

print(mpg.se)

alpha = 0.05

degrees.freedom = mpg.n - 1

t.score = qt(p=alpha/2, df=degrees.freedom,lower.tail=F)

print(t.score)

mpg.error <- t.score * mpg.se

lower.bound <- mpg.mean - mpg.error

upper.bound <- mpg.mean + mpg.error

print(c(lower.bound,upper.bound))For the lazy folks among us - there’s also this quick and dirty way of doing it.

# Calculate the mean and standard error

mpg.model <- lm(mpg ~ 1, mtcars)

# Calculate the confidence interval

confint(mpg.model, level=0.95)Great. Let’s plot this interval on the distribution.

ggplot()+

geom_histogram(aes(x=mtcars$mpg,y=..density..),binwidth=2,fill="blue",alpha=0.5) +

stat_function(fun = dnorm,

args = list(mean = mean(mtcars$mpg), sd = sd(mtcars$mpg)))+

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean(mtcars$mpg), linetype="dotted",alpha=0.5)+

geom_vline(xintercept = lower.bound,col="purple")+

geom_vline(xintercept = upper.bound, col="purple")+

labs(title="Histogram of mtcars$mpg",

caption = "Data: Made from mtcars",

x="",

y="") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(panel.spacing.x = unit(10, "mm"))+

theme(legend.position="none")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=9))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(plot.title = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,15,0))) +

theme(plot.margin=unit(c(0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5),"cm"))

Two things we note here: First, the distribution doesn’t look that normal. Second, geez that 95% confidence interval looks narrow as a result.

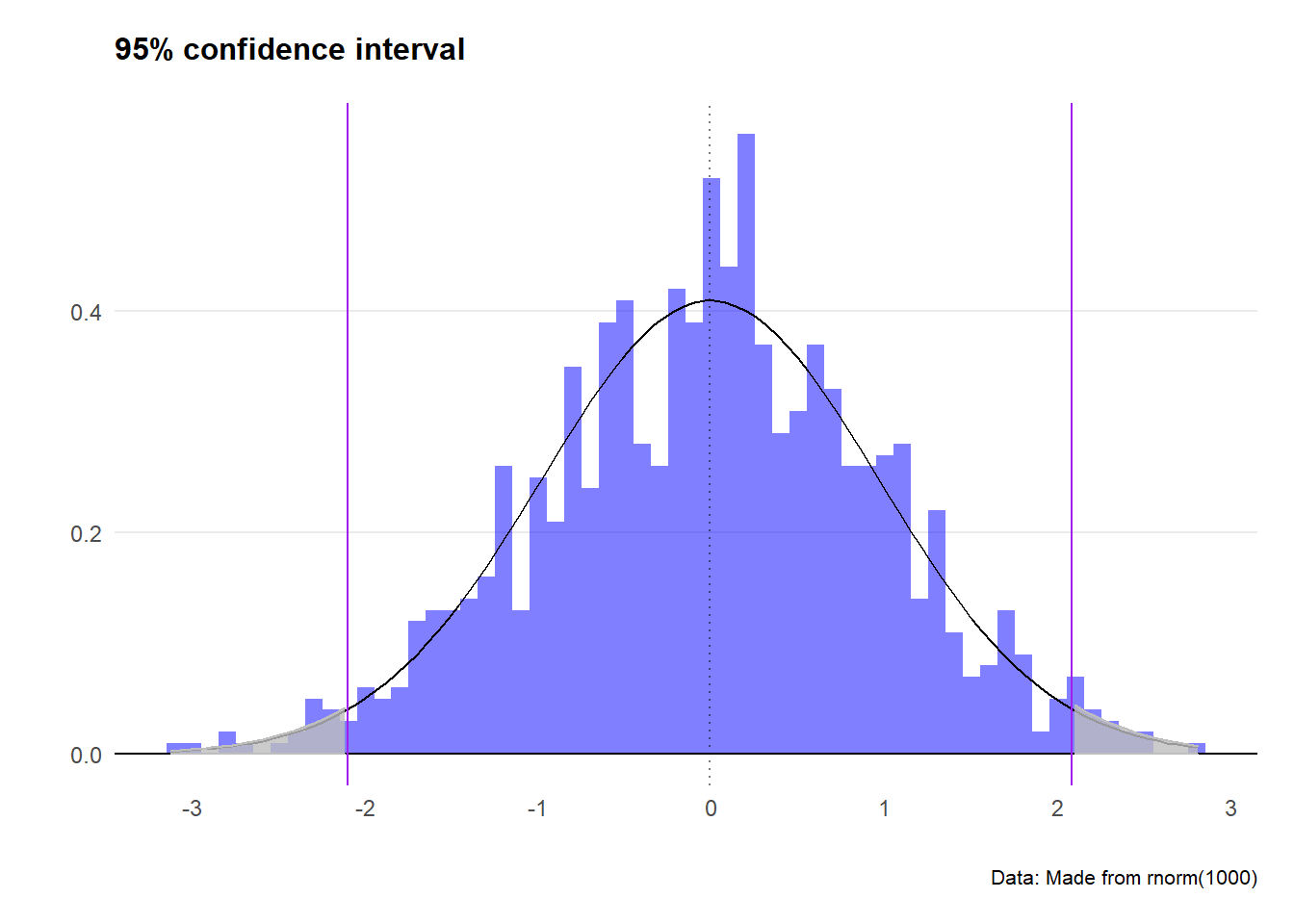

Let’s do the same analysis with an actual normal distribution and see what happens.

set.seed(404)

dataset2 <- data.frame(variable1=rnorm(1000,mean=0,sd=1))

df2.mean <- mean(dataset2$variable1)

print(df2.mean)

df2.n <- length(dataset2$variable1)

df2.sd <- sd(dataset2$variable1)

df2.se <- mpg.sd/sqrt(mpg.n)

print(df2.se)

alpha = 0.05

degrees.freedom = df2.n - 1

t.score = qt(p=alpha/2, df=degrees.freedom,lower.tail=F)

print(t.score)

df2.error <- t.score * df2.se

lower.bound.df2 <- df2.mean - df2.error

upper.bound.df2 <- df2.mean + df2.error

print(c(lower.bound.df2,upper.bound.df2))

#Make a function to colour the tails

upper_tail <- function(x) {

y <- dnorm(x,mean=0,sd=1)

y[x < upper.bound.df2 | x > 1000] <- NA

return(y) }

lower_tail <- function(x) {

y <- dnorm(x,mean=0,sd=1)

y[x < -1000 | x > lower.bound.df2] <- NA

return(y) }

#Plot the distributions

ggplot()+

geom_histogram(aes(x=dataset2$variable1,y=..density..),binwidth=0.1,fill="blue",alpha=0.5) +

stat_function(fun = dnorm,

args = list(mean = mean(dataset2$variable1), sd = sd(dataset2$variable1)))+

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean(dataset2$variable1), linetype="dotted",alpha=0.5)+

geom_vline(xintercept = lower.bound.df2,col="purple")+

geom_vline(xintercept = upper.bound.df2, col="purple")+

stat_function(fun = upper_tail, geom = "area", fill = "grey",col="grey", alpha = 0.8) +

stat_function(fun = lower_tail, geom = "area", fill = "grey",col="grey", alpha = 0.8) +

labs(title="95% confidence interval",

caption = "Data: Made from rnorm(1000)",

x="",

y="") +

theme_minimal() +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(-3, 3, by = 1))+

theme(panel.spacing.x = unit(10, "mm"))+

theme(legend.position="none")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=9))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(plot.title = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,15,0))) +

theme(plot.margin=unit(c(0.5,0.5,0.5,0.5),"cm"))

Great - we’ve got a more sensible looking plot, and greyed out the tails where our confidence interval excludes. We expect out observation to fall somewhere between the two purple lines (or more exactly between -2.1 and 2.1)

7.6 Confidence intervals (model)

Secondly, we can calculate the confidence internal around a linear model. Somewhat similar to above, this process shows us how confident we can be about any single point in the linear estimate (e.g. if it has an enormous confidence interval attached to it… the linear estimate of the value at that point is probably a bit dodgy).

mtcars.lm <- lm(mpg ~ hp, data = mtcars)

summary(mtcars.lm)

predict(mtcars.lm, newdata = mtcars, interval = 'confidence')It’s great to have the raw data - but there’s an even easier way of plotting the confidence interval on a chart: we use the geom_smooth()function.

The syntax in this example is:

geom_smooth(aes(x = hp, y = mpg), method='lm', level=0.95)

ggplot(mtcars)+

geom_point(aes(x = hp, y = mpg), col = "blue", alpha=0.5)+

geom_smooth(aes(x = hp, y = mpg),method='lm',level=0.95)+

labs(title="Building a regression model",

subtitle = "Higher horsepower cars get less miles to the gallon",

caption = "Data: mtcars dataset",

x="Horsepower",

y="Miles per gallon") +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position="bottom")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=8))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(axis.title.y =

element_text(margin = ggplot2::margin(t = 0, r = 3, b = 0, l = 0)))+

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(vjust = -0.5,

margin = ggplot2::margin(l = 20, r = -10)))+

theme(plot.subtitle = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,25,0))) +

theme(axis.line.x =

element_line(colour ="black",size=0.4))+

theme(axis.ticks.x = element_line(colour ="black",size=0.4))+

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position="bottom")+

theme(plot.title=element_text(face="bold",size=12))+

theme(plot.subtitle=element_text(size=11))+

theme(plot.caption=element_text(size=8))+

theme(axis.text=element_text(size=8))+

theme(panel.grid.minor = element_blank())+

theme(panel.grid.major.x = element_blank()) +

theme(axis.title.y =

element_text(margin = ggplot2::margin(t = 0, r = 3, b = 0, l = 0)))+

theme(axis.text.y = element_text(vjust = -0.5,

margin = ggplot2::margin(l = 20, r = -10)))+

theme(plot.subtitle = element_text(margin=ggplot2::margin(0,0,25,0))) +

theme(axis.line.x =

element_line(colour ="black",size=0.4))+

theme(axis.ticks.x = element_line(colour ="black",size=0.4))

For a sanity check, let’s crank up the confidence level to 0.999 (meaning our interval should capture just about all the observations). We see the confidence interval band increases… but not by that much. Why? Well remember how the data isn’t a very good normal distribution? That means the confidence interval function won’t be super accurate - especially at the extremes.